|

Module V: Listening and Disclosure

Section 2: Disclosure

After completing this section, students should be able to:

- define disclosure and explain how we use depth and breadth to measure it.

- describe the eight guidelines for disclosure.

- differentiate the six types of relationships by disclosure level.

- differentiate between, and describe, appropriate and inappropriate listening responses.

- explain the role of perception-checking in effective communication.

Communication is comprised of message flowing to and from each of us. We receive many verbal and nonverbal messages from others, and we are constantly sending some sort of messages about ourselves; recall, “One cannot not communicate.” As we send messages about ourselves, we engage in disclosure. Disclosure (also called self-disclosure) is the act of revealing new information about ourselves. The key to defining disclosure is the word "new." When someone learns something about us they did not previously know, we are engaging in disclosure. Although we often think of disclosure as referring to the sharing of deep, dark secrets, disclosure is a common occurrence. If we are meeting someone for the first time, telling them our name is disclosure; likewise, sharing intimate feelings with a close partner is disclosure.

Disclosure is the substance of building and maintaining relationships. Our relationships are nothing but how we communicate(how we disclose) with another. Whether we measure communication by the quality of verbal disclosure, or by nonverbal disclosure, a relationship is a comfort level of sharing information about ourselves with another person. With people we see in passing, such as the clerk at a convenience store, we have a transient relationship. We only disclose information necessary for the transaction and perhaps a small bit of phatic communion or small talk. With close friends, we may use some phatic communion, but we focus more on disclosing personal experiences, feelings, and thoughts. Each type of relationship is defined by the level of disclosure.

Measuring Disclosure

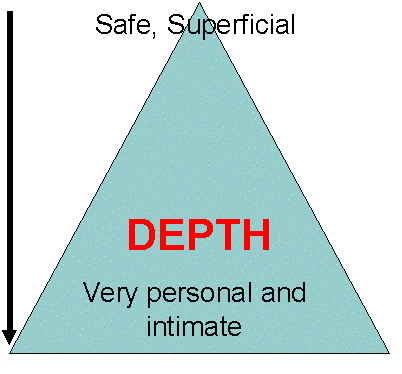

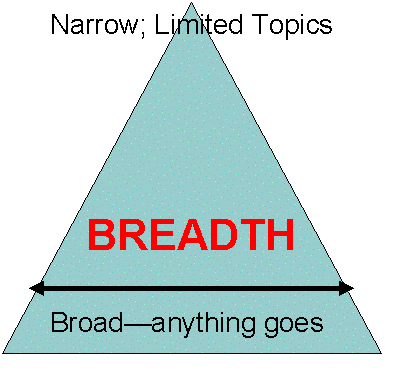

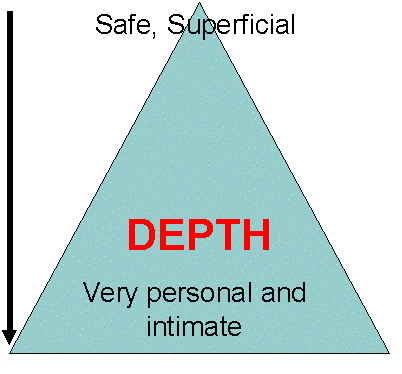

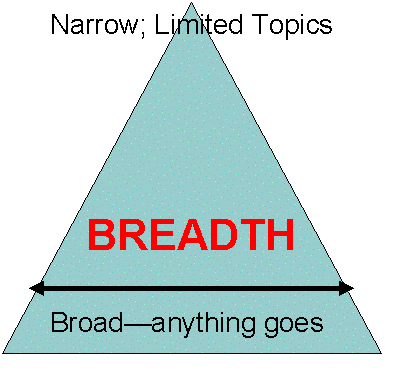

We measure disclosure in two dimensions: depth and breadth.

|

| Image 1 |

The depth of disclosure refers to the level of intimacy or the personal nature of the disclosure. Disclosure can range from very superficial (our name) to very intimate and personal (secrets we hold close). Generally, for us to share intimate details of our lives, we need a close, trusting relationship with the other person.

|

| Image 2 |

The breadth of disclosure refers to the number of topics addressed. We have friends for different reasons: some are for spending time with, some are for dealing with serious personal problems, and some are for just about anything. There are different topics we consider appropriate depending on the relationship. Some relationships are marked by a very broad breadth of disclosure, where just about any topic is okay. Other relationships are marked by their narrow breadth, in which only a few topics are considered appropriate.

Guidelines for Disclosing |

We do not disclose just anything to anyone. Most of us have had the uncomfortable, “TMI” experience in which a person shared far Too Much Information for the nature of the relationship. They entrusted us with personal details we felt the relationship did not warrant. When waiting for a flight at an airport gate, sharing information about a medical ailment to a complete stranger would be inappropriate. We should have a sense of what to disclose, to whom, and in what setting.

1. The Risk/Trust Status. Disclosure can be risky. Risk is the perceived danger of the disclosure. Types of risk can range from extreme (physical violence) to more moderate (laughter or personal rejection) forms. The famous case of Matthew Shepard, strung up on a fence post in Wyoming, put a spotlight on the dangers homosexuals face in disclosing their sexual orientation (Matthew’s Story, 2013). More common outcomes are others rejecting us, ending relationships, or otherwise altering how they see us due to our revelations about past events, values, beliefs, or our nature in general. Even in close relationships, there can be risk of relationship damage, so risk does not necessarily disappear with intimacy.

Risk can be moderated by trust. We rarely stop and consider what it means to really trust another person. Trust is the belief the other person is looking out for our own best interests. We trust someone when we believe they are more interested in protecting and helping us rather than advancing themselves with what they know of us. Generally, as the trust in the relationship increases, the risk drops, and vice versa. The dynamic means we will see risk and trust as inherently related. One criteria we use to determine the appropriateness of disclosure is the risk/trust status of the relationship.

2. Intimacy. Each of us understands what is intimate information and what is superficial, non-intimate information. Generally, we consider sex to be highly intimate; thus, we reserve discussion of sex to those with whom we consider the sharing of such an intimate topic appropriate. A topic such as the weather is generally consider appropriate for just about anyone in any setting. Not everyone has the same idea of what is and is not "intimate." For some people openly discussing financial issues and the cost of big ticket items (cars, homes) is considered very intimate, while for others money and purchases are discussed freely. Thus, we use our perception of the intimacy level of the information to determine the appropriateness of the disclosure.

3. Valence. Valence refers to the positive or negative tone of the disclosure. The tone of our disclosure can range from positive to neutral to negative. Generally, in U.S. American culture, when talking about ourselves, it is considered more socially appropriate to say something negative to avoid being viewed as egocentric. If a group of students is sitting around complaining about classes, there is a social pressure to maintain valence, at least until the valence shifts. In certain groups, the norm may be to confine comments to the positive, like the saying, "If you can't say something nice, don't say anything at all." We consider whether the valence of the disclosure is appropriate for the situation and people involved.

4. Relationship Appropriateness. As mentioned before, we have different relationships for different reasons. We have intimates with whom we share very personal information, and also have casual friends with whom we socialize at parties, go to movies or games, but with whom such personal topics as relationships may be inappropriate. We make decisions as to the appropriateness of the topic depending on whether the relationship is right for a particular topic. In other words, we determine whether a particular person is the right person to talk to about a particular topic.

|

| Image 3 |

5. Role Appropriateness. We present ourselves differently depending on the social role we are fulfilling. Each of us fulfills many different roles. If married with a family, we fulfill roles such as husband or wife, parent, and with our extended families, we fulfill roles such as son or daughter, aunt or uncle, in-law, or grandparent. We have a multitude of roles outside of our families as well. We have specific roles at work, such as: supervisor, teacher, custodian, accountant, or police officer. We quickly learn each role carries expectations of behaviors and actions. We act differently depending on the role we play at any given moment.

6. Context Appropriateness. We vary our disclosure based on where we are engaging in the conversation. Sitting in a classroom just minutes before the teacher arrives is not a good context for an intimate conversation. Fast food restaurants do not provide a good context for intimate disclosure. Instead, we seek out locations providing some semblance of privacy so our disclosure can be contained to those with whom we wish to share our thoughts. We consider where we are in determining whether to disclose something.

7. Disclosure Style. In addition to the variables discussed above, each us tends to a specific, default disclosure style. Our disclosure style refers to our manner of disclosure and are classified as passive, aggressive, passive-aggressive, and assertive. While most of us will lean to a certain style, we will shift around, depending on some factors.

- We will shift disclosure style depending on the other person. If Lamar is someone to whom we attribute power, Shelby may act more passively if she feels Lamar has more authority than she does. If Lamar sees himself as having power over others, he will most likely be much more assertive.

- We will shift disclosure style depending on the topic. When discussing a topic Sasha feels knowledgeable about, she is likely to be more assertive. Yet when discussing a topic on which she is less knowledgeable, Sasha is more likely to be passive. Sasha's comfort level with the topic may affect her disclosure style. With topics with which Sasha is uncomfortable, she may become more passive and quiet.

- We will shift disclosure style depending on the context. Perry is quite assertive at home but may become much more passive at work. When Becky is at a bar she may be very outgoing, even aggressive, yet once she enters a church, she may become very quiet and passive.

Our disclosure style will vary, and, as a result, what and how we engage in self-disclosure will vary.

Passive Disclosure Style: The passive disclosure style is marked by a reluctance to express opinions, needs, and wants in a constructive, healthy manner. In effect, the passive person goes along with others, assuming others have more right to what they want or need than themselves.

- The passive style demonstrates a sense of lower self-respect and exaggerated other-respect, and the default assumption is “you are more important than I am.”

- The passive style avoids conflict or confrontation, attempting to repress feelings of anger, disappointment, and frustration. When a person represses strong, negative emotions the result may be gunny sacking. Gunny sacking occurs when a person suddenly lets go, venting all sorts of pent up anger and frustrations, often including issues from the past.

- The passive person operates on a “lose/win” mentality. They assume they will not get what they want or need and they will lose. The passive person expects the other person to prevail and win. With a passive mindset, they feel it is futile to try to win.

Aggressive Disclosure Style: The aggressive disclosure style is a very emotional style of disclosure, marked by the use of silencers. Silencers are communication behaviors so offensive as to virtually stop communication. These include some obvious ones, such as yelling, insulting, or demeaning, but they also include crying or emotional outbursts. When confronted with silencers, most of us simply want to get out of the situation, so we are more likely to give in to the aggressor to end the aggressive behaviors.

- The aggressive style demonstrates a sense of exaggerated self-importance and low other-respect. They assume they must get what they want or need (they will win), and the other person must be defeated (they will lose). A person with an aggressive mindset and disclosure style focuses on winning over everything.

- The aggressive style ends up creating many interpersonal problems (resentments, hard feelings, or anger) and tends to dismantle healthy relationships.

- To respond to an aggressive person, there are generally two workable approaches. One approach is to call them out on what they are doing. In effect, saying something like, “I will be happy to work this out, but if you insist on treating me this way, I’m not staying here. We can either discuss this calmly and respectfully or not discuss it at all.” If the aggressor refuses to stop their behavior after a straightforward technique is used, then it may be necessary to leave the situation.

The other approach to dealing with an aggressive person is to act very nice, polite, and soft-spoken. Demonstrate to the aggressor their behaviors are not having the impact they desire, and often they will calm down and back down from the confrontation.

Passive-Aggressive Disclosure Style: The passive-aggressive disclosure style is a blend of the previous two. When in a situation, especially one involving conflict or disagreement, the passive-aggressive person will be passive meaning they will simply go along with others, not indicating any disagreement. However, after the time has passed, they will act in some manner, often circular, to ‘get back’ at the person or people involved. For example, if a customer does not like the service they received at a store, instead of addressing the clerk directly, they may put a bad review on Yelp. The customer avoids the direct confrontation in favor of indirect, offensive action. Clearly, the passive-aggressive mode of disclosure does not encourage healthy conflict resolution or relationship development.

Confronting a passive-aggressive person can be challenging. During a confrontation or tense situation, the passive-aggressive personality will at first act passively, often suggesting, “Everything’s fine,” and “There is no problem,” but then afterwards will engage in troublesome behaviors.

Assertive Disclosure Style: The assertive disclosure style is marked by mutual respect, a healthy respect for oneself and a healthy respect for the other person. The assertive person believes they have a right to express desires, wants, and needs, but they also believe the other person has the same right.

- The assertive person is able to separate the person from the issue. In other words, they know they can have disagreements over issues, courses of action, or opinions while, at the same time, maintaining a healthy personal relationship.

- The assertive person works on the assumption all parties have equal rights to “win,” but not everyone wins every time. In other words, if they lose, they do so graciously and respectfully.

- The assertive person feels frustration, anger, or disappointment, but they know acting out emotionally tends to not solve anything and usually creates additional problems. They will work thoughtfully to manage their emotional response in favor of addressing issues rationally and thoughtfully.

8. Reciprocity. One of the most important dynamics in self-disclosure is the concept of "reciprocity." Reciprocal self-disclosure refers to an exchange of similar disclosure levels to establish a comfort level in the relationship. In other words, we "take turns" sharing information about ourselves until we find a comfortable level for a specific relationship. For some relationships, the level of comfort may be quite deep, but for most of our relationships, it is fairly shallow.

Reciprocity is used to send messages about how comfortable we are in engaging in interaction. For example, on the first day of class Mateo turns to Sydney, whom he has never met, and says, "Hi, my name is Mateo." If Sydney is reasonably comfortable with Mateo, she will likely say, "My name is Sydney." A small amount of reciprocal disclosure sends a message from Sydney to Mateo of "it is okay to talk to me." If Sydney ignored Mateo, she would be sending a message of "leave me alone." At various points in a relationship, the dynamic of reciprocity may change. If Mateo and Sydney become friends and she starts talking to Mateo about her ex-boyfriend, Mateo might be uncomfortable with the topic and respond by looking away, changing the subject, or otherwise getting out of the situation.

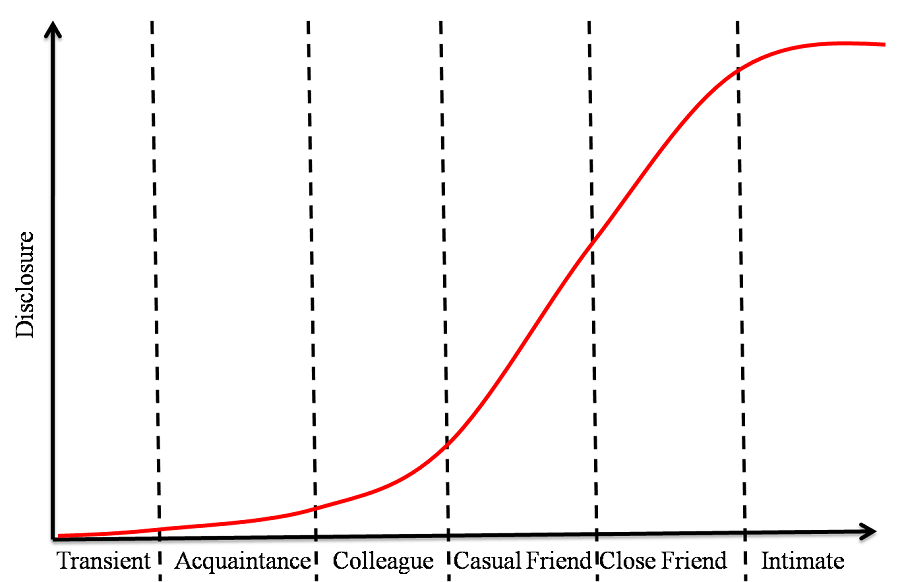

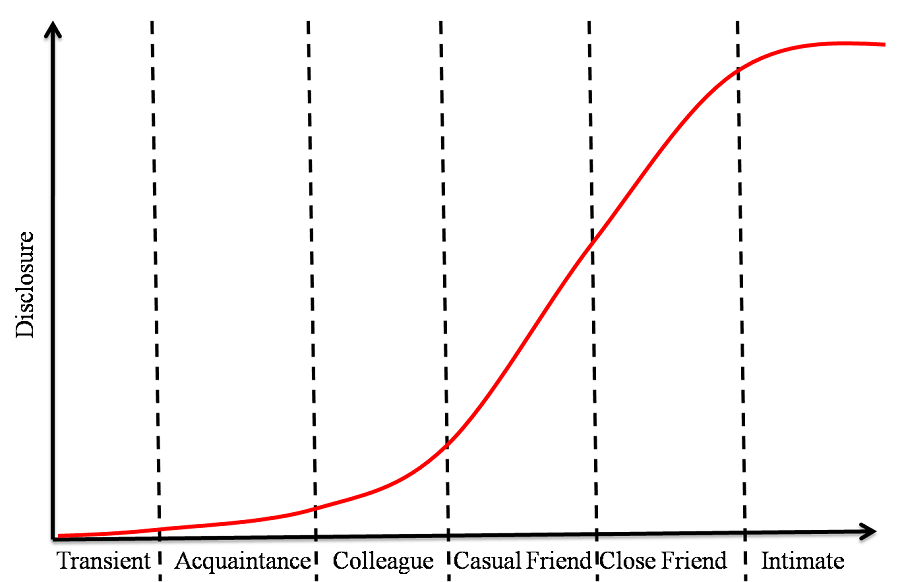

The comfort level of the relationship defines what the relationship is. As can be seen in Image 4, the type of relationship is a function of the level of disclosure, i.e., the comfort level.

|

| Image 4 |

- Transient: A transient relationship is short-lived and intended for a very narrow purpose. In the communication, very little is said, focusing on the purpose of the encounter and perhaps a small amount of phatic communion. An example of a transient relationship is going to a restaurant to eat. Interactions with a server are typically focused on the food with some occasional phatic communion.

-

| Phatic Communion: phatic communion refers to classic small-talk. Talking about the weather, sports, or current events in a casual, superficial manner allows us to interact without having to work to determine an appropriate topic. Phatic Communion make encounters more comfortable and helps us fulfill our social responsibility to connect with one another.

|

Context-Bound: A relationship is context-bound if it only exists within a specific context. For example, if two people who are friends at work often eat lunch together yet do not get together outside of work it is considered a context-bound relationship. |

Acquaintance: An acquaintance is a person who is known because of a particular context. We know acquaintances from class, work, and where we live. We commonly use phatic communion with these individuals, or talk about the context we have in common. For example, if two classmates meet at a store, they might talk about a class assignment.

- Colleague: A colleague is a work-based friendship, and these relationships are heavily context-bound. These individuals are put together involuntarily due to a job or other such activity. Colleagues usually have a modest level of disclosure, and go beyond simple phatic communion. Many colleagues enjoy working together, joking around, eating lunch together, and sharing a certain level of personal information. These relationships are very important in order to facilitate a pleasant workplace climate.

- Casual Friend: Casual friendships are not heavily context-bound, usually occur between people who enjoy each other's company, and may involve a modest level of personal disclosure. These friendships are typically not the person chosen to provide personal or emotional support. While the disclosure is certainly deeper and broader than the previous types of relationships, we do not tend to share very intimate information with our casual friends.

- Close Friend: A close friend is similar to a casual friend, except the disclosure between close friends is typically deeper and broader. Close friends are called upon for emotional support, advice, and to help manage personal life issues.

-

|

| Image 5 |

Intimate: An intimate relationship is one marked by an extreme depth and breadth of disclosure, and level of closeness. In an intimate relationship, few topics are out-of-bounds. While people often equate intimacy to physical intimacy, intimacy in relation to disclosure refers to the relationships with the people closest to us such as a best friend, spouse, or sibling. We typically think of intimate relationships as being visible, in the sense others can see evidence intimate friends are closely connected. Evidence may range from a public commitment, such as marriage, to simply being seen with an intimate frequently.

In maintaining these relationships, we tend to have many transients and acquaintances, and few close friends and intimates. Managing the health of a close relationships takes time. Regular interaction with those closest to us means we need to spend time together reinforcing and maintaining the relationship. Since we have only so many hours in a day, we can maintain only a few close relationships.

When we consider how to respond to a message, we need to realize there are more effective and less effective responses. Whether a specific response is appropriate or inappropriate for a particular person at a particular time is heavily influenced by the nature of the relationship. When engaging in empathic listening, in the attempt to be supportive and helpful to a person going through a tough time, choices of messages range from the more appropriate types to less appropriate response types.

Appropriate and inappropriate responses have several, general characteristics:

| Inappropriate Response characteristics |

Appropriate Response characteristics |

| They divert from the speaker or the issue. The listener may divert to a topic the listener finds more interesting, or even worse, the listener may divert the attention to themselves. |

They keep the focus on the speaker and the issue. Supportive, effective responses let the speaker maintain control of the interaction. |

| They tend to take over the conversation. The listener takes control of the conversation, steering it away from the speaker’s concerns to the listener’s interests. |

They encourage the speaker to continue. The listener lets the speaker know the listener is engaged, interested, and wishes the speaker to take time to express themselves. |

They discourage the speaker from continuing to address their problem. The speaker begins to feel the listener is not truly interested in what they wish to share, so the speaker shuts down and discontinues the healthy process of venting their concerns.

|

They focus on aiding the speaker in solving their problem without telling them what they must do. A key concept in effective, empathic listening is “Listen, don’t fix.” Most of us want to jump to offering solutions to the speaker, yet advice is rarely what the speaker needs. |

| They send a negative, non-caring message. Through shifting the focus to them, the listener sends powerful, negative messages about the speaker and the importance of their concerns. |

They send a positive, caring message. As discussed with attending behaviors, simply attending to the person’s message sends a powerful message of caring and concern. |

Inappropriate Responding

- Minimizing: The use of phrases such as "Don't worry about it," minimizes the importance of the emotions being felt. While we may feel we are encouraging the speaker to “not worry about it,” the fact is they are worried, and they need to process their concerns.

- Blaming: The assumption someone other than the speaker is responsible for the issue at hand. We tend to want to use them to make the speaker feel better by suggesting the situation is not their fault. Realistically, it may well be their own fault, so for us to give the speaker an out by shifting the blame to a third party can shift legitimate responsibility from the speaker. For example, if a friend says, “I can’t believe I failed my math test,” and they hear from a friend, “Mr. Thompson's tests are always too tough,” the speaker may believe they are not responsible for their failure on the test.

- Shifting Topic: When a listener shifts the topic away from the speaker's interest to talking about themselves or a completely different topic. Topic shifting may make the speaker feel their thoughts and ideas are not important. When a listener shifts the topic back to themselves, it can result in a situation of perceived as "one-upping" the speaker. Supportive responses are intended to help the speaker, and not result in a conversational competition. If a speaker says, “I can’t believe I failed the test,” their listener should not "one-up" them by claiming they have failed more tests or done worse.

- Interrogating: Asking a series of questions designed to elicit details about the situation, details the speaker is reluctant to give. Think of the classic interrogation scene on a crime drama on television. In an interrogation, the assumption is one party is guilty and the questions are meant to trap the defendant into confessing. Teenagers may have a similar experience when they come home later than they should, and their parents are waiting for them. The parents bombard their child with questions. The intense questioning or interrogating creates defensiveness, and once defensiveness kicks in, any sort of thoughtful conversation is over.

- Interrupting: Not letting the other person finish their own thought. Interrupting suggests the listener already knows what the speaker is going to say, so the practice is rather patronizing and insulting. The listener may assume they know what the speaker is going to say, but they are wrong about it. Now the speaker has to correct the listener's assumptions, creating another layer of complexity to handle.

- Judging: Evaluating the speaker's actions, thoughts, or feelings. If the speaker feels the listener is judging them, defensiveness will kick in and the conversation is over. Let the speaker talk without making judgments. Always remember, it is the speaker’s job to determine who is to blame and how to respond to the situation.

- Analyzing: Trying to explain to the speaker why things happened. An analyzing response is when the listener attempts to explain to the speaker why they acted as they did, typically using psychobabble. Rosen (1977), in Fast Talk and Quick Cure in the Era of Feeling, defined psychobabble as the ignorant use of psychological concepts (as cited in Project Gutenberg Self-Publishing Press, n.d.). They tend to be superficial, “talk show” type responses. In a sense, the analyzer is a person who has watched a little too much Dr. Phil and now feels qualified to diagnose disorders. An analyzing response can be offensive and dangerous as well. The listener may attribute some sort of mental issue to the speaker, leading the speaker to be worried about more than their original issue.

- Advising: Giving unrequested or unneeded advice as to a course of action. We generally love to tell people what to do, so jumping to advising is a very common type of less appropriate responding. Keep in mind it is the speaker’s responsibility to determine a course of action, but to do so they may need to talk things through. When we jump in and advise them on what to do, we interrupt their process. Listeners should avoid giving advice if:

- they are not qualified to give advice.

- they do not really know enough about the situation.

- the act of advising puts the speaker in an uncomfortable position.

- they might become involved in the speaker's situation.

- they may be held responsible if the advice is used.

- the speaker is clearly incapable of solving their problems.

- the advice may not be wanted.

- it interrupts the catharsis value for the speaker; the “get it off your chest” process.

- it may silence the speaker.

- Incongruity: A verbal message in which nonverbal factors contradict the caring message, such as sarcasm. For instance, a person might say, “Oh, too bad,” in a sincere way to communicate concern and empathy. If they respond in a sarcastic manner, the words suggest caring but the nonverbal communication suggests the opposite. It can be a very demeaning response. Nonverbal communication is more believable and trusted.

- Mental Rehearsing: Focusing only on what kind of response to give, usually with the goal of being glib or dominating. While the person is speaking, instead of listening to the entire message, the listener starts planning how to respond, typically trying to show off by being funny or “deeply insightful.” Mental rehearsing is a listener-focused response style. In contrast, vocalized listening (as discussed in the previous section) focuses on the speaker and the message. Good listeners listen to the content and the feelings within the message, and then respond thoughtfully.

Appropriate Responding

-

|

| Image 6 |

Empathic Resonance: Disclosing personal experiences to the speaker to demonstrate an understanding of their situation; must be brief and focused on aiding the speaker. In reciprocal self-disclosure, the listener assures the speaker (briefly) they understand because they have gone through similar experiences. Empathic resonance helps develop a comfort level in the relationship; the speaker and listener become comfortable with what is being discussed. Also, by sharing similar experiences, speakers and listeners demonstrate an understanding of the feeling component of the situation. If a friend says, “I can’t believe I failed the test,” an appropriate response might be “I sometimes do not do as well as I want either, and it is disappointing.” Most likely the speaker will continue to explain their emotional state, helping them work through the situation.

- Validating: Labeling the emotion(s) one person perceives the other person is feeling. Validating is an excellent, simple response style which strongly encourages the speaker to continue. The listener responds with something like, “You sound angry.” The speaker will most likely respond one of two ways:

- “Yes, I’m angry,” and continue to explain why. The speaker is demonstrating they are working their way through the issue.

- “No, I’m not angry; I’m more disappointed.” Labeling emotion is a very important and healthy part of processing what we are feeling. The speaker is still focused on their issue, but narrowing it down to what exactly they are feeling.

-

Perception-checking. A listener should double-check with the speaker to make sure they have understood what speaker said by perception-checking. We reflect back to the speaker our interpretation of what we heard or saw, allowing them to affirm that we understood them correctly, or to correct us if we misunderstood them. |

Paraphrasing: When the listener restates, in their own words what the speaker said. Paraphrasing is a more extended version of validating in which a listener reflects back more of the substance of what they have said. One important value of paraphrasing is as a perception check, giving the speaker the opportunity to correct any misunderstandings. It also encourages the speaker to keep speaking. As with validating, if one friend says to another, “So you’re upset about the grade you got on the test,” they will most likely respond one of two ways; affirming the correct nature of the perception, or expanding on a corrected interpretation.

- Questioning: Asking relevant, non-threatening questions to discover additional information. As a listener, it is important we understand the speaker’s issue, so asking questions can be a very appropriate response. We want to be sensitive to any reluctance to answer so the questions don’t turn into an interrogation.

- The questions should be non-judgmental. If Jill says to her friend, “Well, did you bother studying this time?” the question fairly clearly implies a judgment.

- The questions should be objective versus directive. If Sam asks, “Why don’t you ask the teacher for extra credit?”, he is attempting to direct the speaker to a specific solution. A better question would be, “Do you think there is anything you can do to pull your grade up?”

- Open-ended questions are better than closed-ended questions. Closed-ended questions, those leading to a “yes or no” answer, limit the speaker’s options in answering. Open-ended questions, such as “What was the test like?”, give the speaker control over how to answer, other than just yes or no.

- Occasionally, we can use a question to suggest an alternative view point and help someone reframe a situation. For example, one friend could ask another, “How much of your overall grade does this test count for?” By reframing, the listener may help the other person consider another way of viewing the situation, while still making up their own mind how they feel about the situation.

When we want to support someone, we use appropriate responding skills. If a friend has had a bad day at work, we might comfort the friend by showing empathy and validating the emotions expressed. It is important we reassure the friend our goal is to help; we provide the support in ways that allow our friend to maintain face. Face is our sense of our reputation or self-worth, so it is important we show we value our friend as an independent, capable person. When we are supporting a friend, the focus should be on the other person and trying to empathize. It is an opportunity to listen actively, encourage disclosure, and paraphrase effectively. By supporting or comforting others, we may enable them to see their situation in a different light while we enhance our relationships with them. While we often think of support at times of stress or unhappiness, we will have many opportunities to celebrate with those close to us. Maybe a friend or family member got a new job, did well on a major exam, or went on an interesting vacation. These types of events also call on us to listen and focus on the other person and their joy.

The substance of our relationships is what we share of ourselves, and how much we let others get to know us. For some relationships we keep our comfort level fairly shallow. For a few relationships the comfort level is much deeper and moves toward developing a close, personal relationship through reciprocal self-disclosure. As we listen, we want to give our focus to the listener. Through purposeful listening we communicate a sense of value and worth in the relationship and we demonstrate their importance to us. In responding empathically, we want to gravitate to more appropriate listening responses in order to encourage the speaker to explore the issue or concern they have, keeping the focus on them, and aiding them in the process of finding solutions themselves.

The terms and concepts students should be familiar with from this section include:

Disclosure

Measuring Disclosure

Guidelines for disclosing

Phatic communion

Context-bound relationship

Types of relationships

Responding

Matthew’s Story (2013). matthewshepard.org. Retrieved 9/9/2013 from ttp://www.matthewshepard.org/our-story/matthews-story

Project Gutenberg Self-Publishing Press. (n.d). Psychobabble. Retrieved 7/5/2017 from http://self.gutenberg.org/articles/eng/Psychobabble#Bibliography

|