|

Module V: Listening and Disclosure Section 1: Listening After completing this section, students should be able to:

Human relationships are built on communication. As we speak and listen, learn about each other, and get to know each other in personal ways, relationships grow and thrive. Our relationships are defined by how we communicate, including what we talk about, when we talk about it, and how we respond. The substance of relationships is how we communicate. Interaction is comprised of what we tell each other (disclosure) and how we attend to each other’s disclosure (listening).

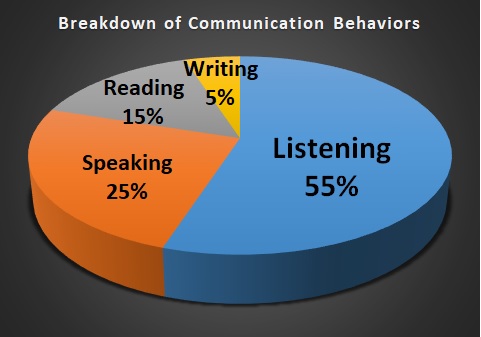

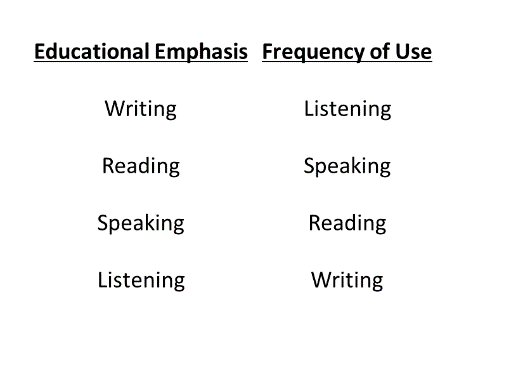

We engage in four communication behaviors: listening, speaking, reading and writing. Of these four, listening is by far the most frequently used. According to the International Listening Association, "Listening is the process of receiving, constructing meaning from, and responding to spoken and/or nonverbal messages" (Verderber and MacGeorge, p. 197). Ever since the first major study to assess listening time, the Rankin study of 1926, researchers have looked at how we use each of these behaviors within our overall communication package (Brownell, 2010). Taking into account a range of studies since Rankin, we can estimate the breakdown of our communication behaviors as shown in Image 1. The specific distribution of our individual communication behaviors will change daily and according to variables such as jobs, interests, and activities.

An interesting contrast is the time we spend on learning each of these behaviors which is directly inverted to the time we spend on each. From kindergarten to college we take classes on improving writing ability. We are taught how to read well into high school. High school students spend significantly less time learning public speaking than they do reading and writing. Listening, which is the most commonly used communication behavior, is rarely taught as a unique, identifiable skill. Listening is the most relational of all our communication behaviors. How we listen to another affects our relationships more than anything else we do. Too often we focus on what to say, when in actuality we need to focus far more on just listening to what the other person is saying. When others focus on us, attending to what we have to say, and really listening and understanding our concerns, they are giving us a powerful message of worth and value.

There are three major purposes for listening: to listen critically, to listen empathically, and to listen appreciatively.

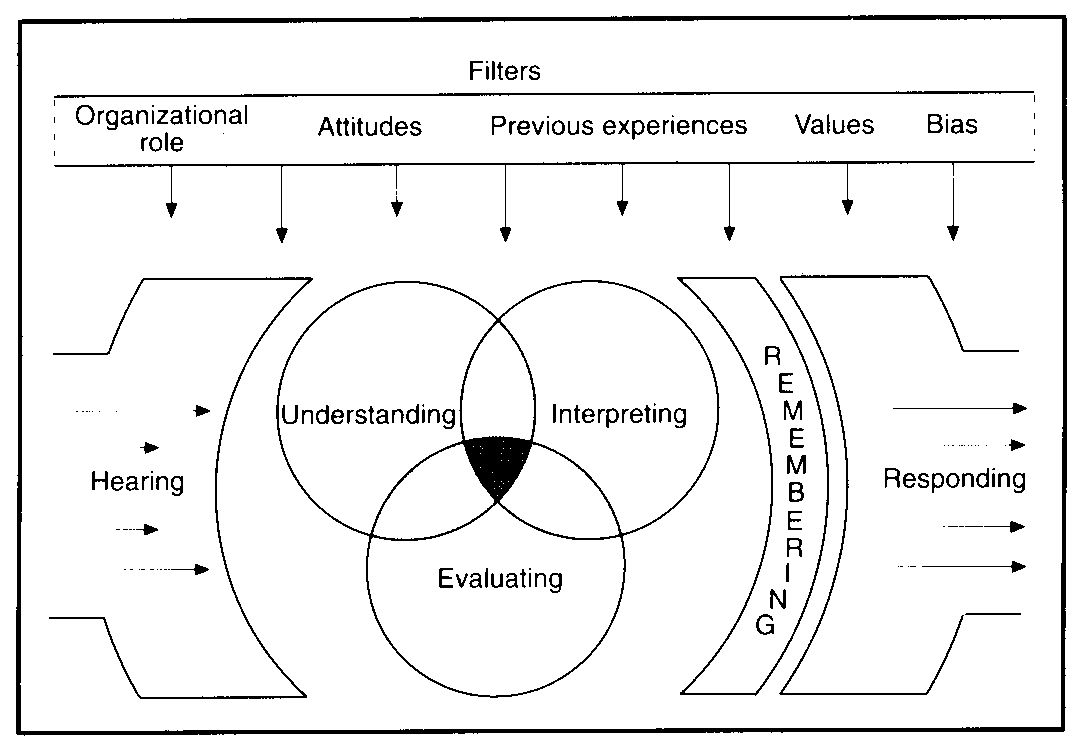

Just like other aspects of communication, listening is a multi-faceted process. Judi Brownell (2010), author of Listening: Attitudes, Principles, and Skills, proposes the HURIER model as a description of the listening process. The HURIER acronym stands for:

The HURIER model is not a series of steps; the model functions to process interdependent components of stimuli.

While the HURIER model illustrates how listening is multi-faceted and complex, we will focus mainly on hearing and responding.

The hearing stage has two parts: the physical process of hearing, and how we focus on the stimuli. We will focus our attention on the latter: how we concentrate on the message the speaker is sending. The more we focus on the message and the core stimuli, we maximize our reception of the message and we minimize external noise; thus, we "hear" more effectively. To increase concentration, we engage in attending, the act of focusing on the speaker. Attending behaviors are the actions we use to focus on the message. The core attending behaviors are summarized in the acronym SOLER.

S = Square Square means we need to face the person as directly as possible. As we turn away from the listener, we direct our focus elsewhere, so facing the person narrows our field to the speaker. However, we must adapt for physical, social, and cultural conventions. Generally, two males in west central Minnesota do not face each other directly for casual conversation; such a face-to-face stance is more often seen as a sign of aggression. Howard Mohr (1987), author of How to Talk Minnesotan, accurately identifies a 45º angle as proper body orientation for males. However, two women speaking face-to-face are generally seen as having a personal conversation, not acting aggressively. While sitting, we may only turn our upper bodies or head, not attempting to radically rearrange furniture. The important point in facing the speaker is they will see we are making them the focus of our attention. Open refers to body posture. Crossed arms, crossed legs, head down, and other like behaviors can be seen as closing off the listener from the speaker. Arms down, head up, and shoulders back serve to open the listener’s posture, inviting the speaker to send their message Lean means to demonstrate interest and focus by leaning toward the source of the message. Leaning helps us narrow our field of focus even more, making the reception of the message easier. The stereotypical back row of students in a traditional classroom, leaning back to the point of being in danger of sliding under the desk, might be regarded as disengaged by their teacher. Yet, the same students viewing a sporting event on TV will likely lean their body posture forward as they engage themselves in a message they find more interesting. Eye Contact is when we demonstrate to the speaker we are paying attention. The speaker’s face becomes the prime field of when eye contact is used appropriately, and it orients our ears to get the sound most effectively. Eye contact works well to minimize external noise by narrowing our focus on the core stimuli, and allows us to focus more effectively on nonverbal visual messages, such as facial expression. Respond refers to the subtle, primarily nonverbal behaviors we use to demonstrate we are paying attention. The head nods, facial expressions, or vocal utterances let the speaker know we are focused on them. While speaking on the phone to someone who does not give typical responses such as “oh,” “uh huh,” it seems strange to attempt to speak to someone without getting feedback. A primary function of the attending behaviors is to help us focus on the speaker, the message, and the actual stimuli. In addition, attending also demonstrates to the speaker we are paying attention to them. By giving our attention to the speaker, we encourage them to continue speaking. If we are being ignored, we shut up; if our message is going nowhere, we quit sending it. We also give the speaker a sense of value and worth. By paying attention, we let them know they are important as a person. There is no greater gift we can give than demonstrating the value and worth of another. We also need to be aware of multiple messages competing for our attention. Dichotic messages often occur when we try to listen to a single individual, yet the noise created by other people, music, or other distractions can take our focus away from the message of our conversational partner. In these instances, we need to find or create an environment in which extraneous noises are minimized so we can focus on the speaker much more intently. Vocalized Listening

While vocalized listening is a good technique to practice, a listener should be careful not to slip too far into a pattern of mentally rehearsing what they intend to say in response to the speaker. As with any communication skill, it takes effort to implement, practice, and attain a comfort level with using such a skill. Over time, and with practice, good listening skills become easier and help us stay focused.

The terms and concepts students should be familiar with from this section include: Purposes of Listening Models of Listening and Hearing

Brownell, J. (2010). Listening: Attitudes, Principles, and Skills (4th ed.). New York, NY: Rutledge.

Mohr, H. (1987). How to Talk Minnesotan. New York, NY: Penguin Books.

| |||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||