|

Module VIII: Public Speaking Section 3: Audience Analysis After completing this section, students should be able to:

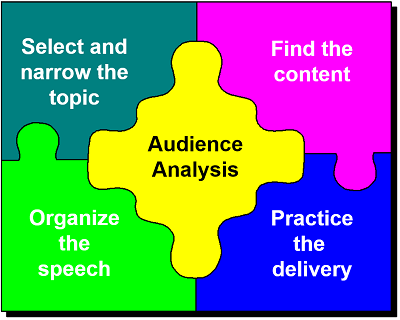

A good way to think of developing a speech is to think of it like a puzzle. There are multiple pieces that all have to fit together, with the driving piece being the audience. The core of a good presentation is an understanding of the audience to whom the speech is targeted. We need to spend some time gaining an understanding of our audience which becomes the criteria to determine the best strategies and approaches to employ.

In order to get a sense of the audience's personality, we do an audience analysis. In such a process, we identify key factors of the audience to help us determine the best approach to take in crafting our message. There are three stages in the audience analysis process. 1. Gathering InformationThe first stage, gathering information, can be as simple as observing who is in the audience, or can be a more involved process of formalized data collection. For classroom speeches, simply look around the room and determine some basic data, such as:

For situations in which the speaker is invited to speak, ask the person extending the invitation about the audience: Who are they? Why are they gathered? What are their expectations? With this basic information, we can move to the next stage, making inferences. 2. Making InferencesAt this stage, we are trying to get a handle on the audiences' collective "personality." To do this, we make inferences. An inference is an conclusion based on evidence and reasoning. An inference is not a guess; a guess is more random while an inference is based on specific bits of information. For instance, if it is December and the wind is blowing, those of us living in colder climates, like Minnesota, will infer, "It's cold outside." That conclusion is based on combining experience with bits of evidence to draw a reasonable conclusion. We can do the same thing with audiences. Now that we have gathered some demographic data, we can move on and make inferences as to what the data tells us about the audience. The most any speaker can consider are the common denominators, those things we believe are true of the vast majority of our audience members.

For example, one common denominator is they are all in attendance for the speech. Why are they there? Are they attending because they came of their own free will, such as attending a religious service. Or are they in attendance because it is mandated by their job? Or is it somewhere in between, such as a college classroom, in which students voluntarily sign up for the class yet are required to attend by the instructor? Knowing the basis of why they are there gives the speaker a sense of what the audience is expecting and the attitudes they are likey holding. For a truly voluntary audience, the speaker has an audience anxious to hear what they say and will generally be quite attentive to the message. For a mandated audience, the speaker is facing an audience that may resent being present and assumes the presentation will be boring or irrelevant. For such an audience, the speaker will need to focus on gaining interest and building relevance. For the blended audience, the speaker can generally assume a degree of interest if the information is presented in an interesting manner. Other inferences can be made as well. For example, given a college classroom of thirty, 18-20 year-old students, the following inferences generally hold true:

Although we know these do not apply to each individual audience member, we are aiming to identify what we think is generally true about the audience overall. By making these inferences, we start to understand what is important to the audience. We have a sense of their values, interests, needs, and expectations which can serve as a target, helping us aim the speaker's message more precisely. We use this information in the final stage of audience analysis, adapting the speech. 3. Adapting the SpeechThe final step, adapting the speech, is the key to using an audience analysis to enhance the chance of success. It really does not matter how well we complete steps 1 and 2, if we do not take the information and act upon it, the speech is much less likely to succeed. In adapting the speech, we are considering how to package the information for the audience; determining the best approach or strategy for accomplishing the speaker's goal. This does not mean the speaker must alter their core message. Instead, it means to take the core message and package it in a manner more interesting to the audience. For example, if doing a speech on sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) to two audiences, 10th graders and college freshmen, the same basic information can be communicated, but it would be packaged differently. For the 10th graders, more formal, medical terms would be used, less humor would be used, and since the speaker needs to consider parents, the speaker should assume the audience is not currently engaging in intercourse. For the college audience, however, more lay terms could be used, more humor could be used, and the speaker could safely assume the audience members, in general, are more sexually active. Notice, the basic information does not change, but the packaging changes. Everything in the speech should be considered as to its fit with the audience. What kind of attire is the audience expecting: formal, casual, or in-between? Is the audience expecting a very animated, active delivery with lots of movement and energy, or are they expecting a more subdued, more thoughtful delivery style? Is the language level to be formal and high level? Or is a more casual language level acceptable? Which sources should the speaker seek out? For an audience with a lot of specific knowledge on the speaker's topic, higher level, very specific, highly qualified sources will be needed. For an audience with less specific knowledge, more casual sources may suffice. If informing an audience of physicians on the latest discoveries in the treatment of lung cancer, very specific medical research sources are needed. However, if informing an audience of college students on the same topic, general interest sources, such as newspapers or magazines, will be sufficient. Everything in the speech must be considered in light of the audience. Some variables may arise as more important than others. For one audience, the quality of sources may be paramount to the success of the speech, yet for another audience, the quality of delivery may be most important. Through carefully considering the dynamics of the audience, a speaker can make self-reflexive choices to increase the chance of success.

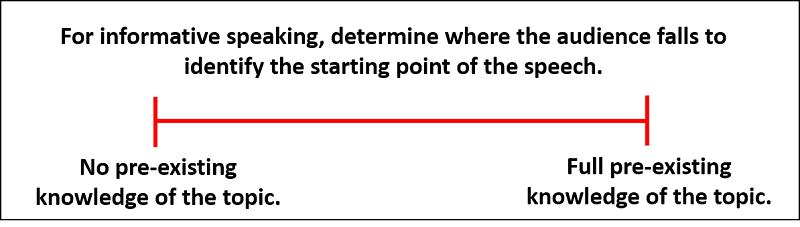

When adapting to an audience for informative speaking, it is vital we have some idea of where the audiences' existing knowledge is on the topic. Remember, If we were to compare individual audience members, we would find a range, but we have to aim for average or middle ground. Once we have an idea of what middle ground is, we use that to determine where to focus the speech. We do not want to focus the speech below the audiences' existing knowledge level. If we do so, the audience may be bored or may even become offended, perceiving the speaker as being patronizing. Likewise, we cannot start the speech above the audiences' existing knowledge as they will not know what we are talking about and will not be able to follow the speech. They will not be able to make the leap from their existing knowledge to the starting point of the speech. The ideal place to start is at their existing level of knowledge, and then we move them forward.

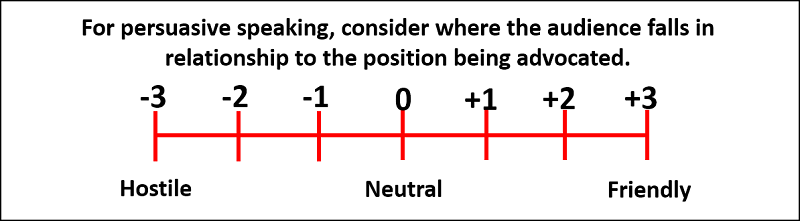

When adapting to an audience for persuasive speaking, it is vital the speaker have an idea of the audiences' existing attitude or position on the topic, and how that compares with the speaker's. As with any audience, we know the attitudes will range, but again we are looking for the average attitudinal position.

Keep in mind that if the audience totally agrees with the speaker's position at the outset, there is little point in trying to "persuade" them as there is no place for them to move, nothing to change, since they already agree with the speaker's position. In this situation, we would give more of a motivational speech to remind the audience of their agreement with our position.

The venue of the speech is the space in which the speech will be given. Each venue will place its own limitations and demands on how the speech will be given. Just as we need to adapt the content of the speech to the audience, we also need to make appropriate plans for the location. The possible factors affecting the speech vary widely, but some common ones include the size of the space, the availability of technology, and arrangement.

First, one thing the size of the space will determine is the need for a sound system. If the speaker is to use a microphone, will it be affixed to a lecturn? Will it be handheld? Will it be a body microphone worn like a headset? Is it wireless or wired? The answer to any of these questions impacts how the speech will be given. For instance, if the microphone is attached to the lecturn, the speaker must remain fixed in one location and must be sure to always keep the microphone in front of their mouth. If the microphone is handheld, the speaker will have one hand occupied at all times, so gesturing needs to be adapted. Second, visual aid capabilities should be considered. If planning to use slideware, is there a projector and screen? How will the speaker get the slides to display: connect their own computer or use one provided by the location? How will they control the slides: a remote? Is the room organized so all audience members will be able to see the screen comfortably?

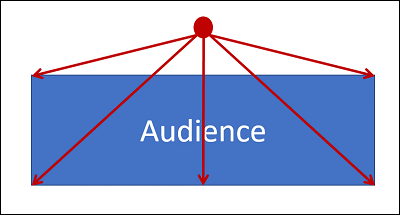

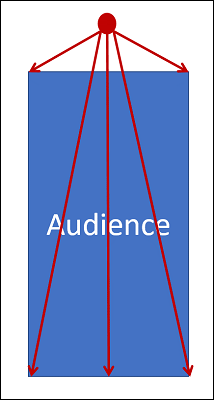

Third, the arrangement of the room may impact how the speaker engages the entire audience. For a flat, wide room, as in Image 8, the speaker will need to focus on scanning far left and far right to take in the entire audience. If possible, the speaker should move across the room to give each area of the audience priority focus for a time. If using a projected visual aid, audience members on the far edges may find it difficult to see, so the speaker will need to focus on making sure all understand what is being show. For a narrow, deep room, Image 9, the speaker will need to adjust volume and work to make sure the message, both spoken and visual, can reach the back row. Visual aids, and ideally the speaker, need to be elevated high enough for all to see.

The terms and concepts students should be familiar with from this section include: Audience adaptation for informative speaking Audience adaptation for persuasive speaking | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||