Module VIII: Public SpeakingSection 6: Incorporating EvidenceAfter completing this section, students should be able to:

Once we have a good idea of what we want to say in the speech, we need to find and include support materials. Support materials refer to any type of evidence, explanation, or illustration we use in the speech to enhance the likelihood the audience will accept and believe what we say.

We use support materials because we need to enhance the credibility, the believability, of our message with the audience. Our audiences will only believe our messages if they can have faith that what we are saying is reflective of the truth or the best ideas. Audiences should believe in us as speakers and in our message. The use of support materials builds our credibility and the credibility of our message. In today's political climate, the ability to identify quality evidence is extremely important. With claims of "fake news" being used to dismiss any information not meeting one's pre-existing beliefs, our ethical obligation to identify the very best sources of information is greater than ever. Compounding this challenge is the plethora of web sites established to advocate certain viewpoints, to cherry-pick news stories for the most sensational tidbits, or to outright fabricate news stories. More than ever we must be critical consumers of information, carefully assessing what we are reading and hearing to separate truth from fiction, and reality from sensationalism. As speakers, we must use that same critial process to insure we are presenting evidence to our audience that can withstand scrutiny. To that end, later in this section, we present the CRAAP test for evaluating sources. When using evidence, especially from outside our own experiences, we rely on credibility transfer. We select good, quality sources we anticipate the audience will find credible, with the hope that by using that source, the credibility attributed to the source will transfer to us as speakers. That is why good, clear source citations are so important. By citing the source, we are giving information to the audience to allow them to establish the credibility of the source and to enhance our credibility as the speaker. There are two broad categories of evidence: internal and external. Internal evidence refers to our own personal experiences, knowledge and opinions. The evidence can be strong if the audience sees us as having expertise in the area. As the audience's perception of the speaker's credibility increases, the speaker can rely more on internal evidence and less on external. However, even highly credible speakers will still use external evidence as well to enhance their expertise. External evidence is the experiences, information and opinion from someone other than the speaker. For external evidence to carry weight with the audience, they must view these external sources as credible.

There are three types of evidence: testimony, examples, and statistics. Each one has its strengths and weaknesses. Testimony

| ||||||||||||

|

|---|

| Image 1 |

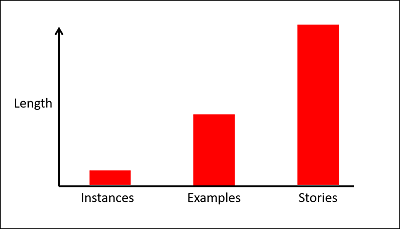

In the middle is the more common example. When using an example, the speaker gives the pertinent details, but does not develop it as a full-blown story. For example, to illustrate a speech on drinking and driving, a speaker might give some examples of individuals who were injured and the long-lasting effects. Saying only the name of the victim would not work, nor would the speaker want to tell the whole story of each person. The speaker gives the important details of each example, enough so the audience understands the point of the example.

Generally, examples are a very effective form of proof with an audience, although by themselves they do not often prove the breadth of the problem; after all, one or two examples do not prove there is a widespread problem. However, due to the human interest we experience with examples, they have the ability, when well delivered, to involve the audience more on a human, emotional level than on a rational, cognitive level.

Statistics

Statistics refer to the numerical representation of data. Statistics can be the most powerful form of evidence to prove the extent of a problem; however, they can also be horrendously misused. In western culture, we tend to believe once a problem has been quantified and expressed in statistics, the statistics are inherently truthful. Statistics can be manipulated, misused, and misrepresented just as any other evidence can be misused. Speakers must be especially cautious when selecting statistics to be sure the numbers come from a quality source and are accurate reflections of reality.

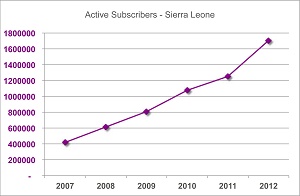

Statistics are used in two ways: descriptively and inferentially. Descriptive statistics describe what was true at a given moment in time. They describe data from the past. The past can be distant, such as in years, or recent, such as hours or days. The statistics reflect what was found when the statistics were gathered. For example, if a poll is taken on a Monday to determine which of two candidates is ahead in a political race, the statistics reflect what was found on the day. If on Wednesday, the media reports one candidate was arrested for drug dealing 10 years earlier, the results of Monday's poll become worthless as they reflected the results prior to the revelation of the drug dealing. When asked what the enrollment of Ridgewater College is, we usually refer to what is called "10th day enrollment." The enrollment of Ridgewater on the 10th day of the semester is used as the official attendance figure, but since students tend to drop out throughout the semester even on the 11th day the number may be wrong. Descriptive statistics report what was found on the day at the time. Descriptive statistics are the type we encounter most of the time.

Inferential statistics are used to predict what may happen in the future. Simply taking descriptive statistics and assuming what they report will be true in the future is a faulty assumption. Rather, inferential statistics are specifically developed to predict behavior. For example, if a study establishes through valid research that as the poverty rate increases crime increases, we could infer if a community experiences a rise in the poverty rate, they are likely to experience a rise in the crime rate. The statistics link behaviors together. Physicians use statistics inferentially daily. As medications are tested, statistical relationships between variables, such as weight, and therapeutic effect are determined. Doctors then use the statistics to determine the appropriate dosage for a given patient, predicting with a high degree of confidence the medical outcome.

Whether used descriptively or inferentially, statistics have some distinct issues:

- The Source: Hundreds of organizations in the U.S. have the goal of persuading the American people and American government to a specific position. Since their goal is inherently biased to one position, statistics released by the organizations are inherently biased. Even if the statistics they release were gathered and processed properly, they will be selective in which statistics they release, publishing only ones supporting their position.

- Gathering/Processing: Gathering and processing statistics have distinct guidelines. If statistics are not gathered using the guidelines, the quality of the statistics is highly questionable. Get statistics from reliable sources to produce quality statistical data.

- Interpretation: It is important speakers use statistics honestly, not inferring conclusions from them the statistics may not support. For example, if a speaker has statistics that 60% of Americans favor hand gun control, they should not use those to claim that the majority of Americans favor gun control; the statistics are specific to hand gun control, not gun control in general.

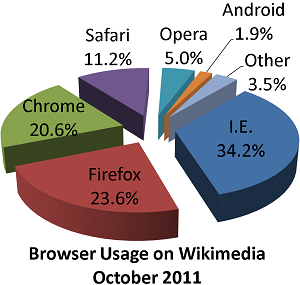

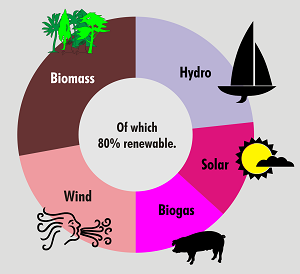

- Presentation: Statistics can be very confusing. The use of graphs helps immensely in clarifying numbers. It is up to the speaker to make sure the audience understands what the statistics are saying.

|

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Image 2 |

Evaluating Sources |

Regardless of the type of evidence used, a core ethical speaker responsibility is presenting the audience with quality, trustworthy information. One way to do this is apply the CRAAP Test to sources. Adapted from “Evaluating Information—Applying the CRAAP Test, “ from the Meriam Library of California Sate University, Chico, there are five criteria to apply to when evaluating sources:

Currency: The timeliness of the information.

- When was the information published or posted?

- Has the information been revised or updated?

- Does the topic require current information, or will older sources work as well?

- Are the links functional?

Relevance: The importance of the information for the speech.

- Does the information relate to the specific purpose of the speech?

- Who is the intended audience for the information?

- Is the information at an appropriate level (i.e. not too elementary or advanced for the needs)?

- Is this the best of several sources reviewed?

- Will providing this information from this source increase the likelihood that the audience will accept the speech content as valid and credible?

Authority: The source of the information.

- Who is the author/publisher/source/sponsor?

- What are the author's credentials or organizational affiliations?

- Is the author qualified to write on the topic?

- Is there contact information, such as a publisher or email address?

- Does the URL reveal anything about the author or source? Examples: .com .edu .gov .org .net

- Will this source be viewed as credible by the audience?

Accuracy: The reliability, truthfulness, and correctness of the content.

- Where does the information come from?

- Is the information supported by evidence?

- Has the information been reviewed or refereed?

- Can the information be verified in another source or from personal knowledge?

- Does the language or tone seem unbiased and free of emotion?

- Are there spelling, grammar or typographical errors?

- Can the accuracy of this source be easily defended?

Purpose: The reason the information exists.

- What is the purpose of the information? Is it to inform, teach, sell, entertain or persuade?

- Do the authors/sponsors make their intentions or purpose clear?

- Is the information fact, opinion or propaganda?

- Does the point of view appear objective and impartial?

- Are there political, ideological, cultural, religious, institutional or personal biases?

Source Citations |

Whenever a speaker uses any external sources, a source citation must be given. One major reason is to avoid plagiarism, presenting others’ ideas and words as one’s own. Citing sources also facilitates the credibility transfer process discussed earlier. If the speaker does not cite the sources, the audience will not know the sources were used; hence, the credibility transfer process will not occur.

In a speech, sources are cited differently than in writing. Obviously, we cannot use footnotes or give a list of works cited at the end of our speech. Instead, the speaker should verbally cite the sources where they are used.

Speakers can be creative and vary how the source is cited and when it is cited. They should be cited smoothly, fitting into the overall flow of the speech. When citing the source, give enough information an audience member could reasonably locate the source and the audience can make a determination of credibility.

Here are some examples of typical source citations:

- “According to the May 3, 2009, Star Tribune article by Dr. Amy Fisher…”

- “Dr. Dana Brown, Director of the Breast Cancer Research Fund, said in last week’s Time magazine, that…”

- “John Gray, in his 1992 book, Men are From Mars, Women are From Venus, explained…”

- “Just last month in Esquire magazine, Stephen Colbert said…”

They are more casual and succinct than citations in a research paper would be. Some instructors require students to hand in a typed bibliography and will usually want it in either MLA or APA format. Students should pay attention to their instructor's expectations.

Key Concepts |

The terms and concepts students should be familiar with from this section include:

Types of External Evidence

- Testimony

- Lay

- Prestige

- Expert

- Paraphrasing

- Quoting Verbatim

- Examples

- Statistics

- Descriptive

- Inferential

- Evaluating Statistics

References |

|

| ||

| Made possible by financial support from Minnesota State Colleges and Universities and technical and staff support of Ridgewater College 2101 15th Ave NW Willmar, MN 56201 (320) 222-5200 |

Keith Green Ruth Fairchild Bev Knudsen Darcy Lease-Gubrud Last Updated |

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |

|

| ||