|

Module VIII: Public Speaking Section 2: The Purposes of Public Speaking After completing this section, students should be able to:

The oldest form of public communication and the precursor to mass media is the simple act of one person rising and expressing their thoughts to the group. Public discourse is the foundation of society; it is how groups of people address and resolve differences collectively and peacefully. With the rise of democracy in Ancient Greece, the value of public speaking gained prominence. A citizen's ability to speak their mind in public was highly valued and a sign of civic engagement. Although we have so many avenues to express ourselves, from in person to online, the ability to craft and share a thoughtful, intelligent message is still an important skill. For a person's career, civic involvement, and political engagement, becoming proficient in public speaking is a highly valuable.

Public speaking has three striking characteristics that set it off from interpersonal communication and small group communication.

First, public speaking is the act of one person speaking to many. Instead of focusing on an interactive nature, public speaking focuses on one person, the speaker, developing and presenting a message to a group of individuals.

Given the fear that most people have of public speaking, it is reasonable to ask why we engage in such an intimidating process. The fear of public speaking is common, often ranked as one of the top fears we have. A Gallup poll from 2001 found that 40% of respondents listed public speaking as their greatest fear, second only to a fear of snakes. Given a choice, people preferred dying over giving a speech. Even with this high degree of anxiety, public speaking retains a valuable place in our culture for several reasons. Societal FunctionsPublic speaking has a long, illustrious history in the United States. The very formation of the U.S. political system and society is firmly rooted in wise people speaking their minds in public settings, engaging in spirited debate and discussion, and working collaboratively to find the best path for the country. Our country is founded on the premise that individuals, working together, can govern themselves. Public speaking is the tool by which this process occurs. Public speaking allows for the relatively quick dissemination of information to a group of individuals.

If a person has much to share with a group, presenting the information via public speaking can be a fast process. A classroom lecture is a typical example. However, a question that begs to be asked is how effective such dissemination is in achieving this goal. In lecture, approximately 5-15% of the material is retained by the student; hence, the speaker (the teacher in this case) must realize this limitation and be willing to use public speaking as a starting point, using other follow up methods to enhance retention of the information.

Public speaking allows individuals or groups to attempt to bring about social or political change. We have a long history in this country of using our freedom of speech to change what we don't like. The women's movement and the civil rights movement of the mid-20th century, and the TEA party movement of the early 21st century are examples of such a process occurring. Individuals see something happening around them they do not like, and they use public speaking to make others aware of the problem and advocate a way to change the situation. Public speaking allows communities to express common goals, concerns, and values. We see speeches of commemoration at Memorial Day, Veteran's Day, and the Fourth of July. The speeches remind us of who we are as a nation, and they express common values. Attending a Sunday sermon is the same. Churches, mosques, and synagogues exist for a group of individuals to share common values and worldviews. The sermon is the central feature which pulls the community members together, the faith leader giving voice to that common world view.

Public speaking allows members of a democratic society, such as the United States, to actively debate issues of concern. We tend to take for granted our First Amendment right to openly and clearly disagree with our governmental structures on issues of concern. We have the legal right, and obligation some would say, to speak out in opposition to those things with which we disagree. Except for advocating violence, we can speak out against our mayors, governors, and presidents, and no one has the right to squelch our voice. When we speak out in a public forum, we are participating in the process of self-governance by exercising our freedom of speech. Personal BenefitsIn addition, to the role of public speaking in our American society, becoming competent as a public speaker benefits us personally. Managing Anxiety Given the anxiety about public speaking, and our need to confront and manage that anxiety, we build self-confidence. Accepting and working with our speech anxiety gives us experience in facing situations in which we are being judged and evaluated. Learning how to confront fear in public speaking gives us tools to use to confront fears in other situations as well. Managing Our Self-Presentation

We learn to monitor and manage our self-presentation. Since the vast majority of communication occurs nonverbally, a competent public speaker knows how to manage their entire physical package to present themselves most effectively, confidently, and powerfully. Just as with confronting our anxiety, being able to self-reflexively manage our self-presentation carries over into all aspects of our professional and personal lives. Although talent and ability is a significant part of career success, communication ability sets people off as especially competent and professional. The ability to engage in effective self-presentation can be a deciding factor in getting a job, being successful in the job, and advancing in our careers. Packaging Information for Others We learn how to package information to benefit others. Good speakers are highly receiver-oriented. We are very concerned about giving thoughtful, well organized, easily followed, and engaging presentations. The ability to create messages fitting these standards will serve any of us well in a variety of professional and personal settings. Many people have good ideas, but not everyone can communicate them well to others. In public speaking, we learn how to package our message to best fit the audience we have at the moment.

Unfortunately, for most people our exposure to public speaking has left us with a distorted view of what makes a "good" speech. Virtually anytime we ask a class, "What is the first thing that comes to mind when you think of listening to a speech," the answer is "boring." This does not have to be the case; it is the job of the speaker to make choices that directly influence how interesting or boring a speech is going to be. As speakers, we have the obligation and ability to choose how effectively and dynamically we will present ourselves and the information to the audience. We can give interesting, dynamic, energetic, and engaging speeches. Each of us has experienced teachers who were boring and monotone, but we have also experienced teachers who were dynamic and energetic. The latter group chose to make the speeches (lectures) more interesting. To make a speech more interesting and effective, we need to understand what makes a good speech:

The public speaking situation is quite different from interpersonal communication and small group communication. The degree of advanced planning, of conscious decision making, and of communicator responsibility is much higher when giving a speech. We have been taught when a person goes to the front of the room to speak, the speaker is now "in charge" of the event. We must meet that expectation, take charge of the event, and fulfill our responsibilities for success. Speeches are only as good as the audience thinks they are; the speaker must rise to the challenge of presenting a good speech.

When developing a speech, we need to know why we are speaking. Even before considering the topic, we need to know if our purpose is to inform, to persuade, to entertain, or if it is a special occasion. Speeches to Inform Speeches to inform are those in which we are aiming to enlighten or to further educate the audience, but in an objective, non-directive manner. We provide the information about the topic to the audience, but we are not directing the audience to believe, feel, or act in a specific manner.

Speeches to PersuadeSpeeches to persuade are those in which we are aiming to influence the audience in some fashion. They are subjective and highly directive. The speaker has a bias toward a specific belief, attitude, or action, and the speaker works to direct the audience in what to believe, what opinion to have, or what action to undertake. In persuasion, the issue of ethics becomes paramount. Some students erroneously believe that speakers always have to give both sides of the issue to be ethical, but that is not true. When Lisa shops for a car, she knows the salesperson is out to persuade her to buy; thus, she expects messages designed to urge her to that action. As long as the salesperson gives accurate, verifiable, and truthful information, there is no ethical violation. It is our job to provide the audience with the most accurate information we can find, and to present that information honestly, not distorting it. We must cite our sources to give due credit, and the topic should be one that can be justified as beneficial to the audience, not just to the speaker. There are three types of persuasive speeches.

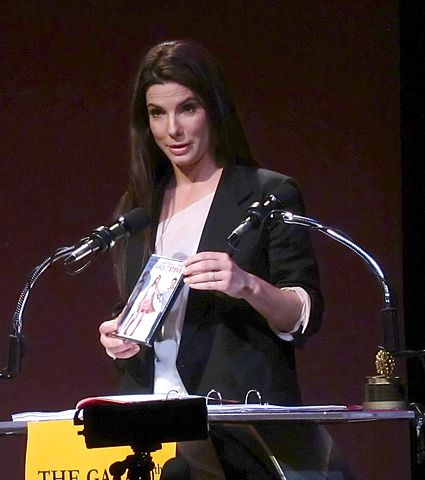

The three types of persuasive speeches build on each other. If Yousef is going to give a speech of actuation calling for the audience to donate blood during Ridgewater College's annual blood drive, he will need to show the audience there is a need for blood (a belief), that donating blood is a good thing to do (an attitude), and how to participate in the blood drive (an action). Speeches to EntertainAlthough not commonly done in an introductory Communication Studies class, there is a third general speech purpose: a speech to entertain. We would hope all speeches are entertaining in some fashion, whether through humor, interest, or seriousness, so the audience found the speech engaging and intriguing. A true speech to entertain, however, is one in which the primary focus is to generate laughter. In other words, they are speeches intended to be funny. These are still speeches in that they are organized, have a clear structure, and flow well, but they have as their overall goal the creation of laughter in the audience. The speaker usually has an underlying serious informative or persuasive point, but it is explored and developed through the use of humor. Commencement addresses, especially by those delivered by comedians or comic actors, like Tom Hanks, are typically structured this way. The speaker has a serious point to make but develops it in a humorous manner. These are common at events such as celebratory dinners or awards banquets. Special Occasion Speeches

A special occasion speech is just what the name states: speeches given at special events. This is actually a very common type of speaking. Special occasion speeches are designed to fit the specific event at which they are being given. While each one has its own unique guidelines, the key point is to develop the speech consistent with that occasion. Some common special occasion speeches include: Eulogy: a speech given at a funeral or memorial service to honor the deceased. Introduction: a speech given to introduce a speaker to an audience. Toast: a speech given honoring a person or group, such as a wedding toast. Giving an Award: a speech given to bestow an honor on a person. Accepting an Award: a speech given to communicate appreciation for an award. Commencement: a speech given at a graduation, typically addressing the past (the work done to acheive the goal) and the future (challenging the graduates to learn more, help others, get involved in social issues, or otherwise continue personal growth). Generally special occasion speeches are fairly short and focused on the event at hand. Humor is commonly used, even with many eulogies, but only when appropriate for the event and audience.

The terms and concepts students should be familiar with from this section include: The Value of Public Speaking

Gallup. ( 2001, March 19). Snakes Top List of Americans' Fears. Retrieved from http://www.gallup.com/poll/1891/snakes-top-list-americans-fears.aspx

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||